Labor Day blues

Walking the picket line, speaking up to bullies at work, keeping your integrity

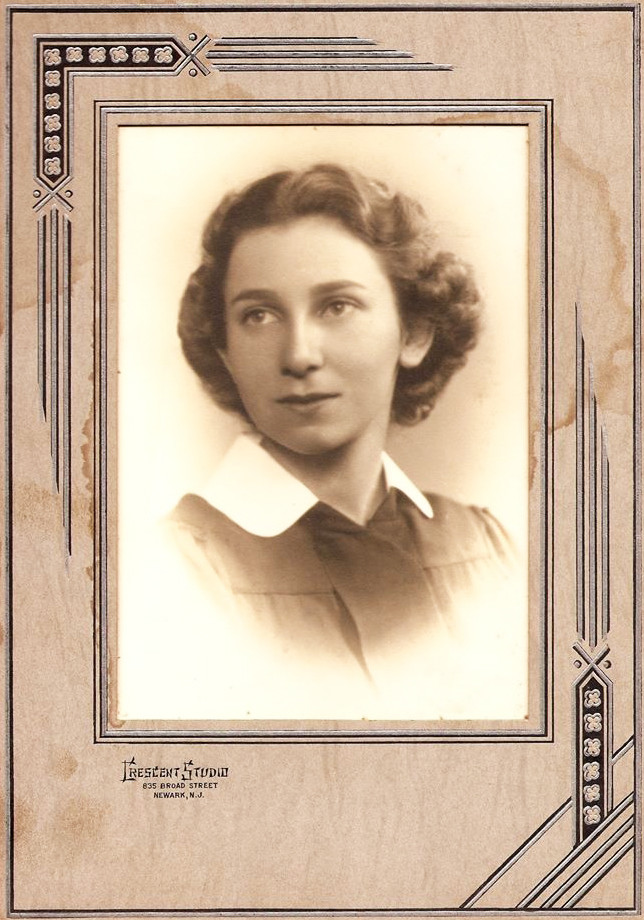

PROVIDENCE – Nothing could have predicted that my mother, at age 49, would become shop steward of her union of social workers at a community agency, leading a strike in 1970, reshaping her understanding of the politics of who gets, what, when and how much.

She was a graduate of Syracuse University, where she had been a cheerleader. She married at age 21. In her 20s and 30s, she was a prototypical suburban housewife, who often found time to volunteer, working with seniors at a local community center at what was known as “The Leisure Lounge.”

After the family business that employed my father was sold, she went back to school to earn her MSW at the University of Connecticut at the age of 42, with three children ages 11, 14 and 17, creating a two-income family.

There was an awkwardness when she took her first job in New Jersey, where our family had moved, when colleagues at Jewish Family Service asked her where she had gone to school, and she replied: “UConn.”

They heard her response as “Yukon,” which only got corrected when someone in the lunchroom asked her what was it like to go to school in Alaska.

The strike took on a note of bitterness, in which the elders of the Jewish community were aghast at the audacity of the social workers to strike for better wages. Imagine. At the reception line at services for the Jewish New Year that year, the rabbi refused to shake her hand, turning away. The most pious are often the most petty.

News coverage of the strike was non-existent, until the strikers opted to have a pet monkey join them walking on the picket line.

As she got older, my mother became much more outspoken, if not radicalized.

In doing so, she reshaped my view of what it means to be willing to stand up for what you believe in, challenging those who are the authority figures, and keeping your integrity in tact, with a certain resoluteness and civility.

To be explicit, the central themes in sharing her story on Labor Day are: 1.) the people who actually accomplish things in most organizations and workplaces are underappreciated and undercompensated; and 2.) most of the gains that people have made, and by proxy, society has made, come from a willingness to stand up against tremendous social and economic pressure.

If I could, I would have liked to interview my mother to capture her thoughts on what it was like to become a shop steward of her union; unfortunately, she died in a car accident in 1980, so I am left to share my own stories about my interactions with bosses.

Are you tough enough?

I would like to believe that some of my willingness to stand up and say no came from her, although I am not sure whether it was more related to nurture rather than nature.

Unlike many of my colleagues in the news biz, I have a history, not often shared in public or listed as part of my curriculum vitae, that speaks to my survival skills working at some “tough” jobs now often featured on TV reality shows, when I was unable to support myself making a living as a writer.

My parents, including my mother, always hoped that I would some day come to my senses and become a lawyer, and forget about being a writer, which they called “an avocation, not a vocation.”

More than once I banged nails and sawed timber in a construction job, hired as a day laborer as a favor by a friend who built log homes, earning $6 an hour. After my first two days on the job, he called me up to ask if I was hurting. I told him, stoically, not really. “Well, I hurt, Richard, and if I hurt, you need to hurt, too.”

The next week proved to be an absolute hell at the worksite; I was driven beyond what I thought my physical endurance level was. When I got home, I didn’t have the energy to take my clothes off or eat dinner; I promptly went to sleep, waking up at 6 a.m. the next morning, and drove off to work again.

When the boss called later that week to ask: Was I hurting? I responded, “I hurt, I hurt so bad. I hope it rains tomorrow.” My boss laughed and laughed, and during the next three months on the job, he kept repeating it, like a mantra: “Do you hurt, Richard?”

The idea that a person should work hurt, or play hurt, as a way of proving one’s toughness, is a silly, destructive way to have to prove your worth.

No shame

I have also collected unemployment a number of times, to keep my head above water, when the job market bottomed out. I never felt a shame in that, only anger when some relatives questioned my work ethic.

I have worked numerous times as a cook – as a line cook, as a grill cook, as a sous chef – in restaurants in Seattle, in Washington, D.C., in Northampton and Greenfield, Mass., when I ran out of money.

It was always grueling work, often done in appalling conditions, where you were always exploited to the fullest extent of your talents. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “A personal meditation on the nature of work on Labor Day 2017.”]

Bad behavior by bosses

Some of the worst bosses I have ever worked for were in writing and communications jobs: one boss was an alcoholic who was closeted in his office days at a time, refusing to interact with staff; another was a crook who delighted in bullying women; a third once grabbed me by the throat and threatened me; a fourth asked me to do her homework assignment for college class; the list of bad bosses goes on and on.

The bottom line is that, without protection, often provided by a union, workers will find their wages cut, their hours increased, the job descriptions changed, and extra hours demanded without any recourse.

Without access to health insurance through employment, the middle class has disintegrated, a condition documented by Kathleen Hughes and Tom Casciato in a series produced by Bill Moyers, “Two American Families,” over 20 years. [See link below to the TV series.]

For many Baby Boomers, the ability to retire becomes more and more like a bridge too far to cross.

The bottom line

So much time and energy has been devoted to talking about the future economy and what will spark new job creation and the need for better skills training for workers entering the 21st century economy.

I often wonder if that same kind of training should be mandatory for bosses, too. What are the consequences, if any, when bosses lie and deceive their employees? Who will hold them accountable for their broken promises? And when will employees be given a voice in decision-making?

For all the talk about how the recently enacted tax cuts would spur a new spurt of economic growth, most of the money received by corporations who benefited has gone into stock buy backs and bonuses for executives, and very little has gone into wage increases for employees. The stock market may be booming, but many households are barely breaking even – and that is not because of a lack of a work ethic.

One last story in honor of Labor Day: A few years back, the owner of a publication I worked for celebrated what I believe was its 25th anniversary with a big bash at a Newport mansion. The owner, when he took the stage to say a few words, thanked his family and the advertisers from some big companies for their continuing support. Not a word of thanks was said to any of the employees, as I recall. So it goes.

All too often, the workers are invisible to the owners and the bosses. When Rhode Island economic development officials hold news conferences at the Slater Mill in Pawtucket, they often fail to mention that the enterprise was built on the backs of young women laborers. The first factory strike in America occurred on May 26, 1824, in Pawtucket, when 102 women laborers who were power loom weavers, mostly between the ages of 15 and 30, protested plans by the mill owners to decrease their wages by 25 percent and to add an additional hour of work each day, by blocking entrance to the mill.